Foreign Ownership Restrictions and the Agricultural Land Reserve

Grocery prices have risen significantly in the last several years. Perhaps the decrease in oil prices might help…

The past decade can undoubtedly be recognized as Canada’s strongest period with respect to real estate appreciation. Significant demand for all asset classes, particularly residential, has led to unprecedented pricing.

While ‘strongest’ might be an uncomfortable word for some, it really depends on which side of the fence you reside – the ownership or the non-ownership side.

Real estate has now become such a point of discussion that one cannot open a newspaper or entertain guests without the subject of real estate values or ownership rearing its head. Hand in hand with the discussion on real estate values invariably comes the topic of foreign ownership. While most discussions in the mainstream media have tended to focus on the residential market, there has recently been considerable interest devoted to an asset class that could impact a country’s population in ways that might ultimately be more significant than rising housing costs. This asset class is agricultural land.

Grocery Prices on the Rise

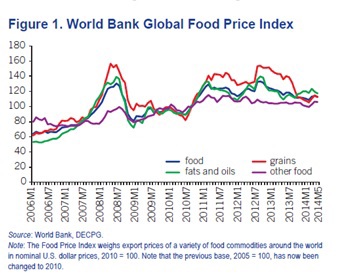

In case you haven’t noticed, the world food markets have experienced several price shocks brought about by supply side interruptions partially due to unforeseen weather related events. According to the World Bank’s “Food Price Watch” May 2014 issue, international prices of food increased by 4% between January and April 2014. Food prices have consistently increased over the last eight years, coupled with several supply shocks, as shown in Figure 1.

World Bank Global Food Price Index

The vast majority of households have noticed the recent rise in food prices – from milk and meat to baked goods and kitchen staples. This trend is expected to continue, considering a rising population, changing weather patterns, and higher operating costs (fuel particularly). Securing a nation’s food supply has been a top priority for many leaders, not to mention the increased interest by private agricultural REITS, food producers, and cooperatives.

So how does the residential real estate market in Vancouver relate to Agricultural Land? The simple fact is that global foreign investment in real estate is significant, and the control of agricultural land is one that can have far more impact than the change in supply of office space or apartments in downtown Vancouver.

Agricultural land purchases by foreign companies and state-owned corporations have increasingly been in the headlines, and for good reason. China, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Canada, Qatar, Russia, Japan and Western European nations have all been busy acquiring farmland in other nations that are either more food secure, financially unable to develop their lands, or lack appropriate regulations to prevent the wholesale divestiture of an incredibly important national asset.

If foreign ownership of residential real estate has the potential to (at least partially) skew housing values, what impact will foreign ownership of agricultural land ultimately have on a nation’s food supply, food prices, and security?

Tracking Foreign Investment

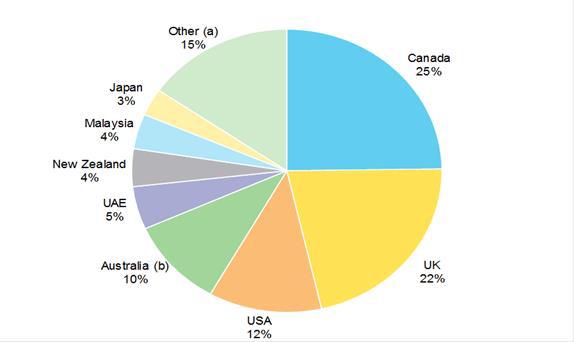

With a strong agricultural sector, Australia is an example of a country that lacks appropriate government regulations regarding foreign investment in agricultural land and agricultural businesses – otherwise classified as Rural Land. Recent mass acquisitions of Australian farmland by purchasers from Canada, the UK, the U.S., the UAE, Malaysia, Japan, and others have caused a public uproarand have several political parties campaigning for stricter policies regarding agricultural land purchases by foreign investors.

According to the Australian government’s “Foreign investment in Australian Agriculture” report, 11 percent of Australia’s agricultural land is now foreign-owned, with the highest proportion (24%) in the Northern Territory. Furthermore, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), of the 400 million hectares of agricultural land in Australia, nearly 50 million hectares have some level of foreign ownership (June 2013), an increase of 11 percent from the 44.9 million hectares reported in 2010.

Foreign Investment in Australian Agriculture

The Australian Greens Party is campaigning to strengthen government policies regarding foreign investment in agricultural land by lowering the reviewable threshold for private companies and taking into account cumulative purchases. Currently, Australia’s Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) only reviews investments in land in excess of AU $248 million (unless a sovereign fund is involved), and is not required to take into account cumulative purchases by the same foreign entity that, when combined, comprise $248 million or more. We have made several attempts to contact the Foreign Investment Review Board in order to better understand the demand for Australia’s agricultural land; however, they have been unwilling to provide any additional insight other than what is publicly available.

Both these policies might be subject to change as there appears to be a widespread mistrust of any foreign investment in farmland in Australia. Lowy Institute’s 2012 poll found that the large majority (81%) of Australians are against the Australian government allowing foreign companies to buy Australian farmland . There are also more general concerns that government-owned foreign buyers may out-compete local entrepreneurs in agriculture, and that they will not follow the environmental standards in maintaining the farm land, thus jeopardizing its productivity in subsequent ownership.

The largest investors in Australia’s agricultural land were countries with mature agriculture sectors, able to bring the latest technology and management skills for this sector. Interestingly, the country with the largest investment volume in Australia’s agriculture sector between 2007 and 2012 was Canada, with nearly a quarter of the total investment volume, followed by the UK and US.

In 2010, Alberta Investment Management Corporation (AIMCo), one of Canada’s largest pension fund managers, acquired an interest in 252,000 hectares of forest land in Australia by purchasing Great Southern Plantations for A$415 million. For the moment, this land remains forest, but AIMCo plans to partially transform its asset into agricultural land.

But should we really care if foreign interests control significant amounts of agriculturally productive land? That’s an argument that partially depends on the country, and the nature of the investor, I suspect.

In the case of many African nations that lack the financial wherewithal to develop their lands, perhaps it might be seen as a benefit. At least the host country will benefit from access to employment, a potentially increased food supply, improved technology and industry knowledge, access to capital, and, most importantly, productive agricultural land.

In the case of Australia, a country that is already well-capitalized and a net exporter of agricultural products, the benefits are not as clear. While some might argue that land acquisitions by Canada (as an example) are being made as purely economic investments, much like how any fund would acquire an income producing asset (or stock, or bond), the future ramifications could be considerable. When we consider climate change, population growth, and energy cost increases, a country’s food security starts to look a little different.

In 2013, the Chinese Ministry of Environmental Protection identified 3.3 million hectares (roughly the size of Belgium) of farmland that had moderate to severe pollution and was deemed unfit to support agricultural use.

3.3 million hectares of land in China is so polluted it is unfit for agricultural use.

Some have estimated the cost of remediating this land at over $800 billion. With a population of almost 1.4 billion, it’s not surprising that China has been looking to expand its agricultural land holdings through state-owned enterprises (SOE) to diversify its agricultural land holdings and feed its population. As mentioned, in the case of Australia, state owned enterprise investments remain a politically sensitive issue – the Foreign Investment Review Board must approve each SOE investment regarding agricultural land in Australia.

With an estimated 80 million new mouths to feed each year, the planet’s largely unrestrained population growth will continue to put pressure on our developed farmland.

Canada’s Agricultural Land Policies

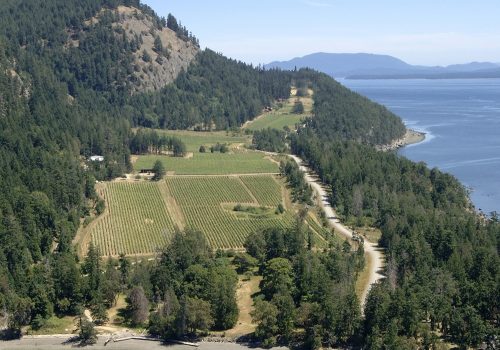

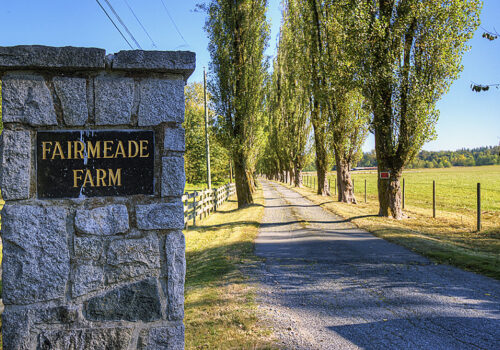

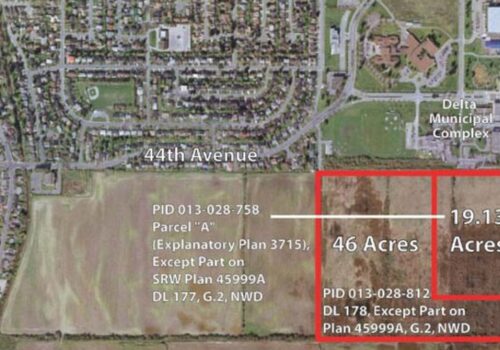

So what about Canada? Do we protect our agricultural land and our food production? As outlined previously, while there are no restrictions in British Columbia with respect to foreign ownership of real estate, we do regulate agricultural land. This is done through the Agricultural Land Reserve, or ALR. The ALR is a provincial land use policy that preserves our agricultural land for agricultural uses. At least this controls the fixed supply of agricultural land and will prevent it from being utilized for non-agricultural uses.

What about other provinces? It turns out many of our provinces have fairly stringent regulations when it comes to foreign ownership of land, with respect to agricultural land. Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Quebec and Prince Edward Island all have regulations in place that are intended to prevent foreign ownership of agricultural land (although PEI is a little different).

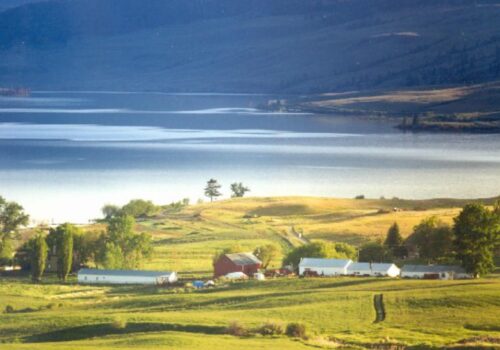

Saskatchewan has historically had the most stringent regulations.Until 2002, ownership of agricultural land in excess of 320 acres was limited to Saskatchewan residents only. This law was changed in 2002 to permit all Canadian residents the right to own farmland in the province. Saskatchewan’s policies appear to be strictly applied. Discussions with Mark Folk, the general manager of the Saskatchewan Farmland Security Board, indicated that its board reviews all purchases of farmland in the province – this is reportedly more than just a cursory review.

Want to buy farmland in Saskatchewan? Only if you are Canadian.

It is not surprising to see Saskatchewan has the policy it does. Let us not forget that this is the home of Tommy Douglas, the founder of Canadian Medicare and one of North America’s first democratic socialist governments. Saskatchewan’s political position might have influenced the creation of the Saskatchewan Farm Security Act in 1974, much like the B.C. NDP government created our ALR in 1974.

Alberta and Manitoba also have similar regulations to Saskatchewan that restrict the ownership of agricultural land to predominantly Canadian interests. In Quebec you need to be a Quebec resident for at least 366 days before you are eligible to purchase farmland. On Prince Edward Island you need to get approval to purchase more than 5 acres (not just farmland) if you are not a provincial resident.

Although provincially regulated, farmland in most Canadian provinces can’t be acquired by foreign entities. It would have been interesting to sit with policy makers at the time various policies and acts came into being to understand the factors that led to their creation and the general climate at the time. Certainly the recent global surge in farmland acquisition has had significant impacts in other parts of the world, with respect to raising the question of foreign ownership.

Despite a whopping 28% increase in values in 2013 alone, from a global perspective, Saskatchewan farmland is considered to be very affordable. Couple this with a stable Canadian government, strong financial system, and many other factors, and it’s easy to understand the interest in our agricultural sector. Saskatchewan land prices would undoubtedly be much higher today if not for Saskatchewan’s policy; yet they have still gone up. Determining one single factor for their increase is challenging, but at least part of the increase is certainly due to the change in the policy in 2002 allowing any Canadian interest to acquire land. We would be looking at a very different picture if there were no restrictions at all.

It is interesting that many of our provinces felt it was important to develop foreign ownership restrictions on agricultural land. The protection and control of our food supply is deemed to be important to the economic welfare, the social fabric, and the safety of many of our communities, yet when it comes to other asset classes, there is no such consideration.

Without respect to subsidies or tariffs on agricultural products, goods, for the most part, enter into the supply of global trade. Regardless of who is producing these assets they should ultimately have a similar retail price within given economic regions. As a Canadian consumer, the price of wheat will generally be the price of wheat regardless of who is producing it, and, most significantly, where it is produced – until supply and demand variables change considerably.

Perhaps what we should be considering when thinking about real estate is the ‘product’ that is consumed. The product produced by agricultural land can be consumed globally, but the same can’t be said about residential housing. If foreign investment raises local prices beyond the reach of those tied to the local economy, at a certain point there are no more tradeoffs and concessions that certain economic classes can make. That is, those that are financially unable to afford housing will simply leave the region. Housing is not a good you can import – unlike apples from Washington State or grapes from Chile, goods that are also produced here.

Our politicians enacted effective legislation to protect our farmland – and food security – from foreign investment and control. This protection was obviously put in place with good reason. Some would suggest that Vancouver, and perhaps Toronto as well, is facing a crisis in housing affordability. Whether or not domestic housing values are related to foreign investment has not yet been objectively determined. The fact remains that real estate is becoming increasingly globalized, and with this globalization comes a host of factors that will continue to shape our policies, communities, and, quite possibly, what we eat. Whether or not we enact legislation to control these factors is food for thought.

Sources

Researched and authored by: Alan L. Johnson of Colliers Unique Properties

Questions? Please contact us

http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/publication/food-price-watch-may-2014

http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=11309648

http://www.gowlings.com/KnowledgeCentre/article.asp?pubID=3229